Bridging Contemporary Art and the Sublime *

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

There are three primary schools of thought when it comes to spirituality in secular education:

- The first group believes we should be praying together and reading religious texts in our public schools.

- The second group believes that religion and spirituality are just too complicated and too delicate to address in a public school, so it’s best to avoid these topics altogether... And I totally understand where they’re coming from — especially considering the terrible history of acculturation, oppression, and indoctrination in our educational system.

- The third group, however, believes that spirituality and religion are complex cultural phenomena that permeate nearly every facet of our lives, whether we see them or not, and we would be doing our students a tremendous disservice to not address, critique, and explore them. These spiritual dimensions of teaching and learning are being explored by a group of educational scholars, and I’m interested in joining that conversation.

In my classroom I also aspire to introduce my students to contemporary artists — because I find value in exploring artists who are working today, and responding to the world we currently live in. Learning about Rembrandt is awesome, but Rembrandt didn’t know anything about smart phones, or Twitter, or what it feels like to have Donald Trump as a President.

So this curricular experiment is an endeavor to bridge two of my aspirations — exploring spirituality, and exploring contemporary art with my high school students.

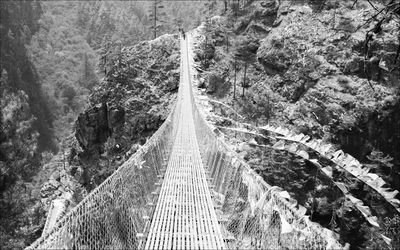

>> I went to Nepal on a field study with a team of art educators led by Dr. Mark Graham. Our intentions were to study Hindu and Buddhist art-making and iconography. We trekked through the Khumbu region of the Himalaya for two weeks, walking beside porters and yaks with bells. As we walked through the rhododendron forests, the steep mountain passes, past ancient mani walls and prayer wheels covered in snow, we were welcomed into monasteries by generous Buddhist monks, who taught us about mindfulness and presentness.

Perhaps it was my unique company (being surrounded by a team of art educators) but while I was there, everything was art.

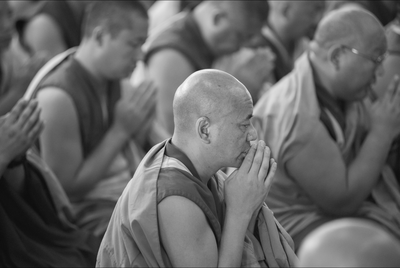

When I saw monks sitting in quiet meditation, paying attention to the present moment, I remembered Marina Abromovic, sitting with strangers in a moment of strange and beautiful availability.

When I saw Buddhist monks spend days creating sand mandalas, only to sweep them up and throw them in a river as a meditation on Impermanence, I remembered John Baldesarri, who cremated all of his work from 1953-1966.

As I followed behind Buddhist monks on narrow mountain trails, with hands clasped behind their saffron robes, I remembered Richard Long, who has endeavored “to make a new art which was also a new way of walking: Walking as art (Tufnell 2007, p.39).”

When I stumbled into Buddhist and Hindu temples, I noticed collections of rocks, beads, shells, candles, and pre-packaged processed food. Just by being in the temples, they became carefully curated collections of holy objects, and I remembered artists like Mark Dion and Fred Wilson, who disrupt the ways museums gather and display their collections.

As I watched Tibetan pilgrims circumambulate the the Dalai Lama temple, spinning prayer wheels along the way, I remembered William Lamson ceremoniously watering a patch of desert soil in Chile for 3 months, waiting for rare pink wildflowers to bloom (they never did).

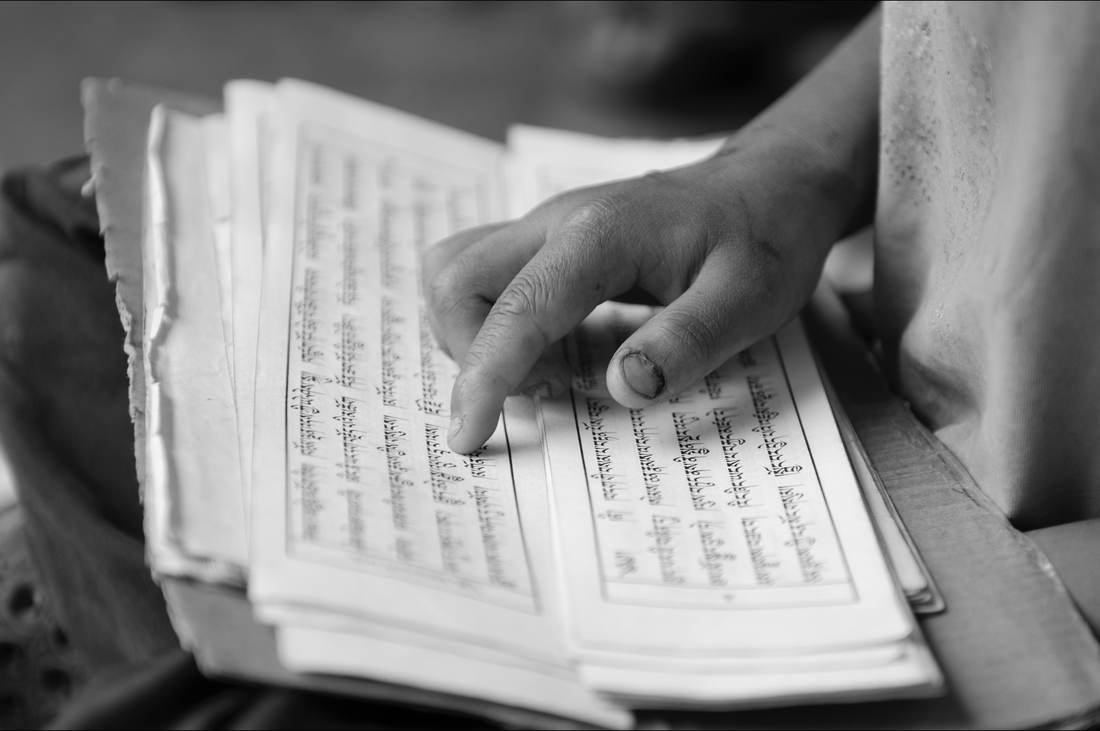

When I saw young Buddhist monks practicing their prayers and mantras, stumbling awkwardly over the ancient Tibetan script, I remembered Janine Antoni stumbling awkwardly in her studio, as she practiced tightrope walking for a performance piece called Touch.

Perhaps it is a stretch to pull these disparate worlds together.

Perhaps mining contemporary artwork for elements of spirituality is misguided.

Perhaps these artists never intended to create work with a theological subtext.

But perhaps we can create new openings for generative dialog by tinkering with these communities of practice, and perhaps each genre of work can teach us something about the other.

After returning home, I began exploring these connections with my students. First, we developed a broad definition of spirituality as a class.

Students had beautiful and surprising definitions of spirituality:

They said that spirituality is:

Being alive in the here and now

Anything that gives you comfort or peace

What science can’t define.

That feeling that everything is gonna be okay

The absence of fear

Something that makes you whole

Something that makes you wonder

A recognition of purpose

Something that pulls people together

And a struggle to better yourself and your community

To their definitions I also added one by the scholar Patrick Slattery, who suggests that spirituality could be an embracing of the irrational or intuitive. Jacques Derrida also reminds us that the great spiritual traditions of the world teach us to call certainty and secularity into question.

After creating a broad definition as a class, I encouraged students to find something spiritual in the work of a contemporary artist. They used Art21 as a starting point, and branched outward from there. Students began making surprising connections that were rich and unexpected.

At the culmination of this unit, my students and I made work together. We challenged ourselves to create work that could be contextualized as both a spiritual practice and a contemporary art practice.

Our critique day at the end of the unit was such a good day. The student work was surprising and complex—many of the students pushed themselves into unfamiliar territory, and explored new genres while grappling with big ideas and questions about their own spirituality. A few students said that their art practice had given them a new vocabulary for their spirituality.

The student work was surprising and complex. For example, this student was fascinated by the typographic experiments of the designer Stefan Saggmeister, and created an installation in the woods using fabric and a staple gun. The fabric spelled the word “Truth” when viewed from one precise angle, and the student documented his installation by taking video while rolling past on a longboard. His work led to discussions about the subjective nature of spiritual truth. The student wrote: “My spirituality is based on searching for truth, in whatever methods necessary, and there’s not one set way to do it. I’ve only found truth by changing my perspective.”

This student was intrigued by the work of Heather Hansen, who blends her identities as dancer and fine artist to create performative drawings. The student found something spiritual in the way Hansen approaches her work. The student wrote, “In spirituality, repetition is a common theme. Repetition of prayer, repetition of breathing, repetition of practice. Heather Hansen uses repetition to turn vague shapes and movement into something defined and beautiful, and that is what inspired me to do a movement piece of my own.”

Another student drew from the work of the contemporary artist Thomas Hirschhorn, who creates monuments and obscure collections as a form of artistic inquiry. She created a two-screened video installation that explores the spiritual dimensions of her life. She wrote, “I see people being drawn to religion and spirituality in hopes of finding answers and explanations to their questions — but for me, I often find that the further I walk down a spiritual path, the more questions arise. This piece is not only a collection of objects, but a collection of questions — a search for answers I’m hoping to find.”

By attempting to build a bridge between contemporary art and spirituality, we opened up spaces for generative conversation and critical dialog. The prompts pushed our work in new directions and invited us to reframe our own conceptions of the sublime.

A student wrote, “I think by not talking about [spirituality] in classrooms, we accidentally perpetuate misconceptions people have about others beliefs. Rather than not talk about our beliefs, I think educators need to strive to create tolerance between their students and unfamiliar (and sometimes scary) ideas. By doing this, students would not only become more educated and humane citizens, but also learn how different people use spirituality to become better people.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed