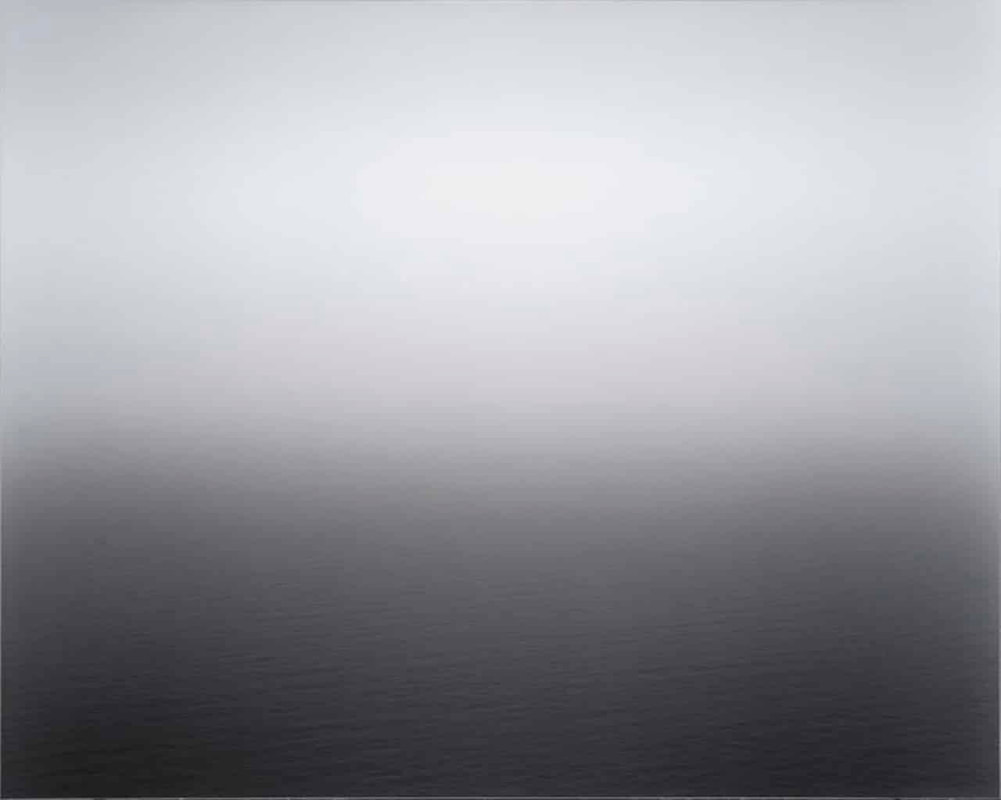

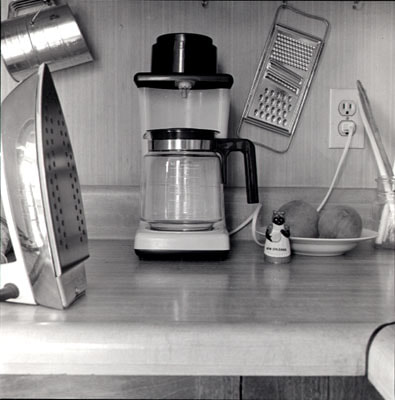

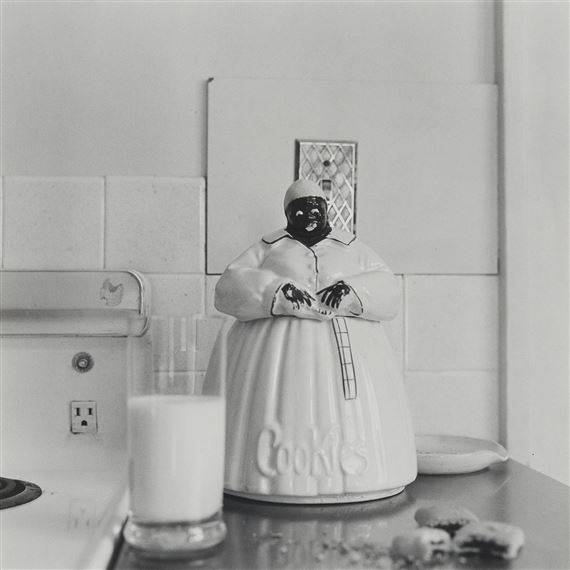

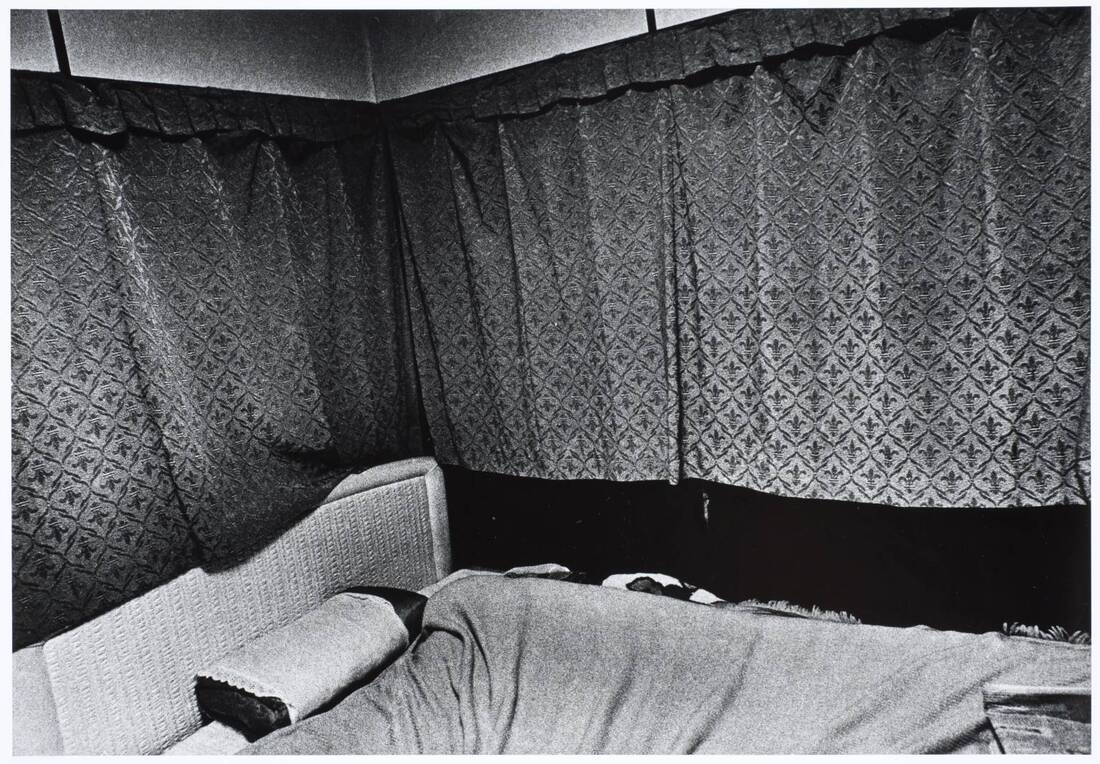

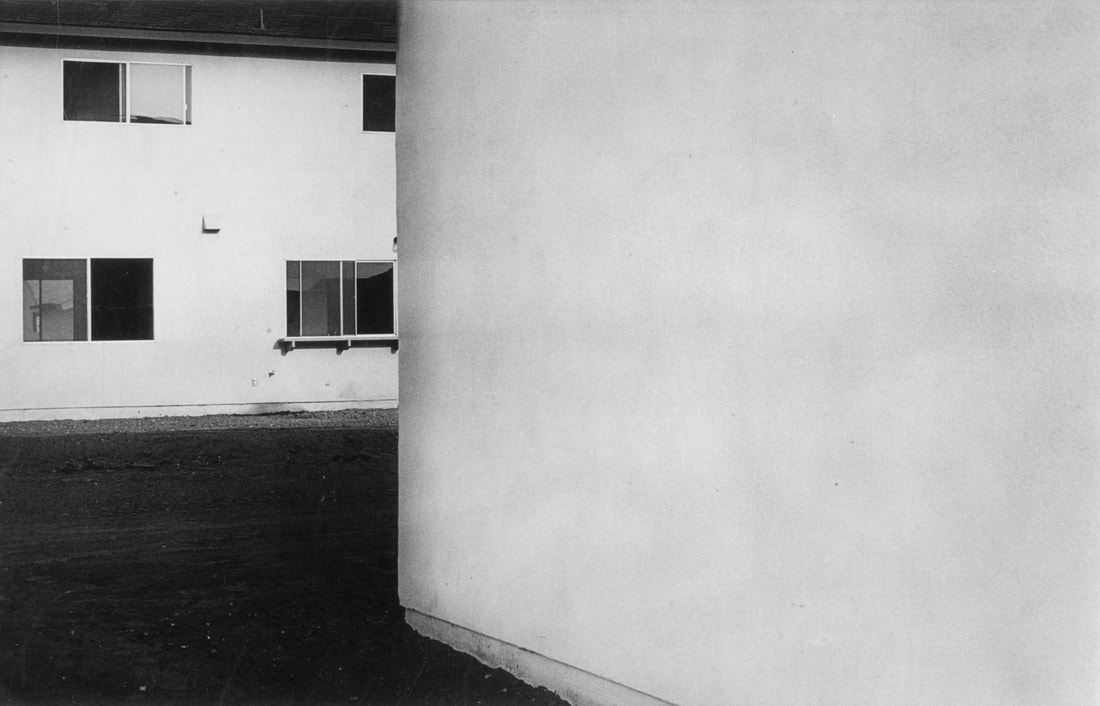

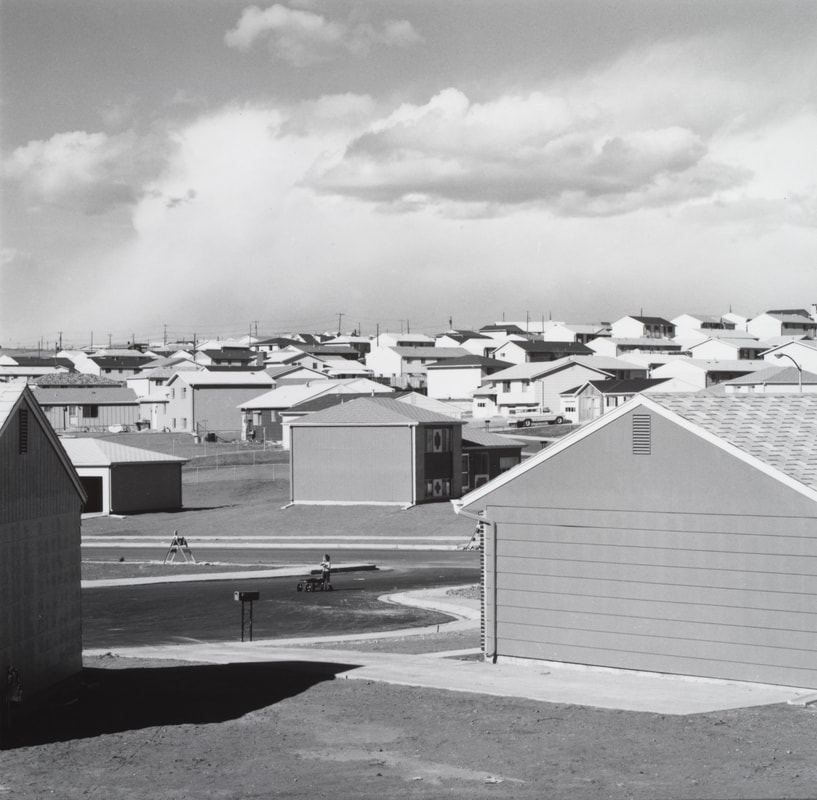

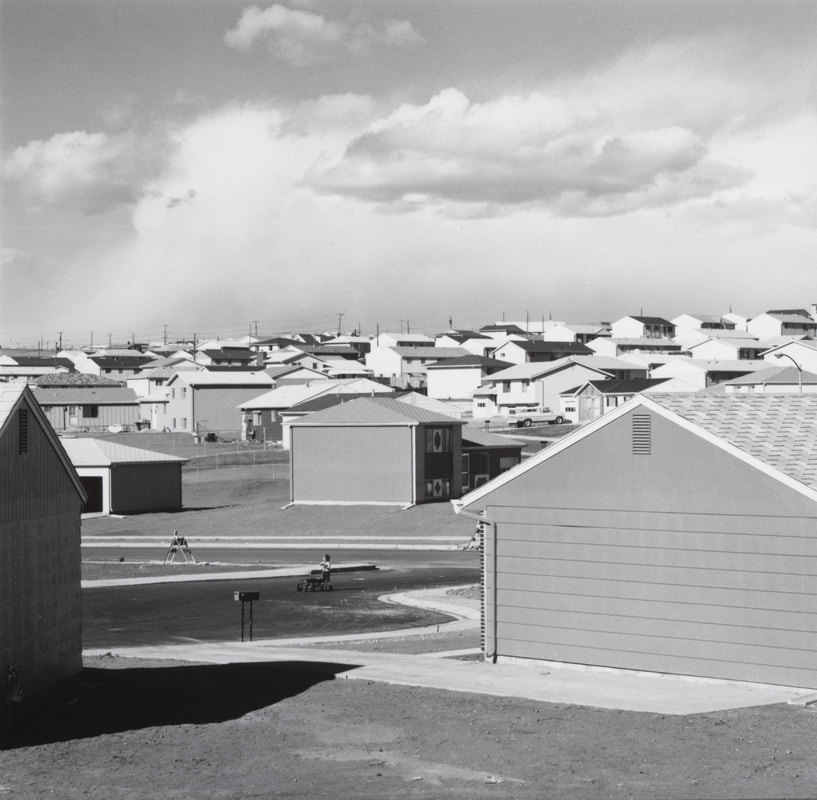

There's really no such thing as a photograph of nothing.

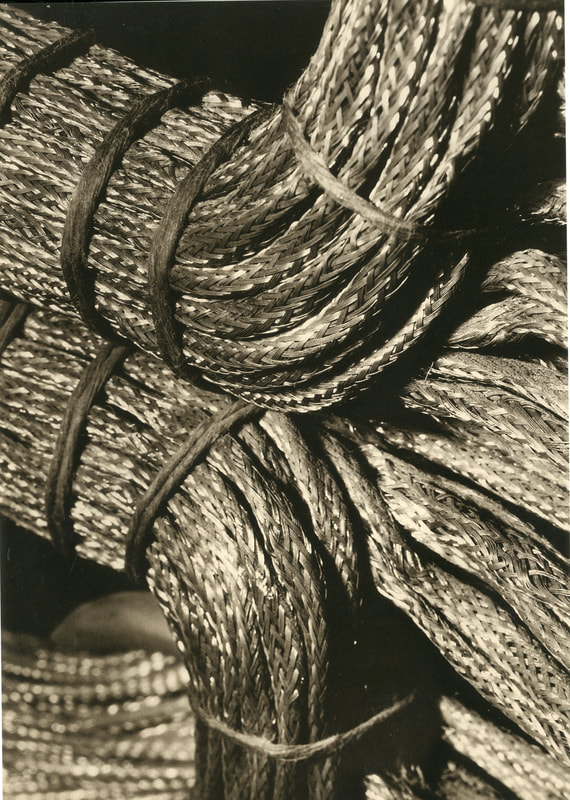

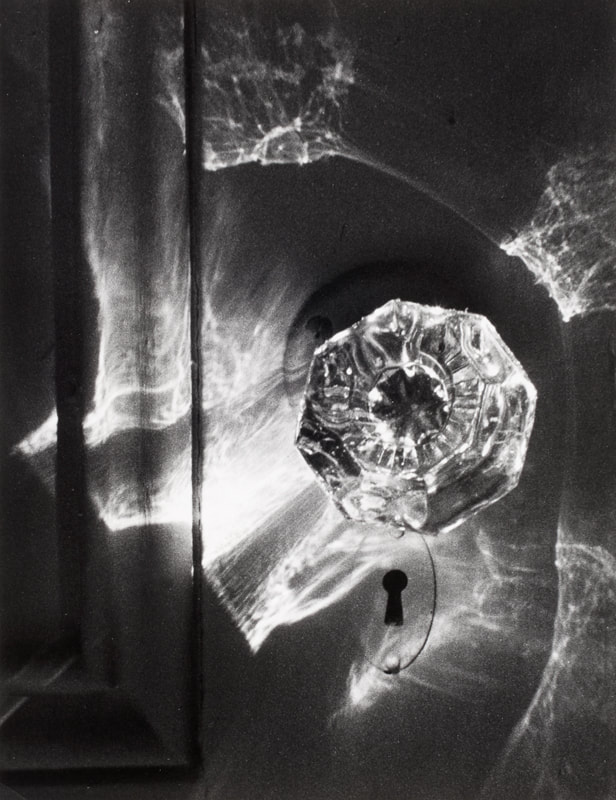

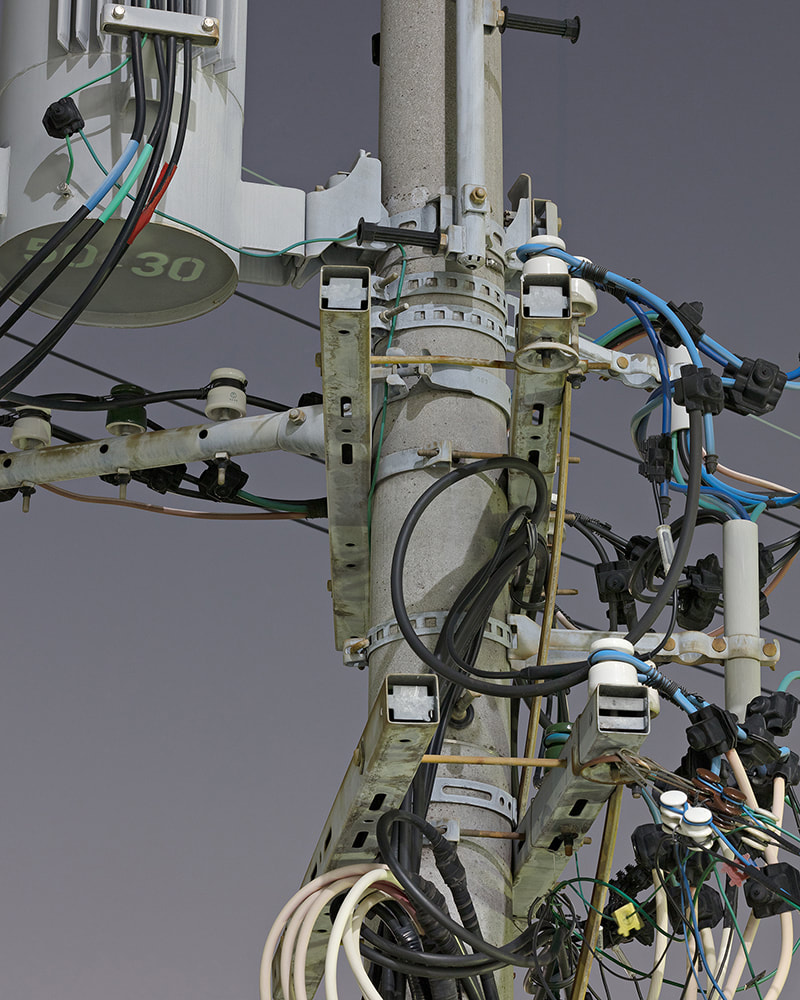

This is a framing for understanding images that might defy easy reading. These images, either through abstraction or overt banality, resist simple interpretation. They ask us to look, again, at something overlooked.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

This article sheds some light on the allure of what could be termed "Photos of Nothing" >>>

When most people think of a photograph they think of images, taken with a camera, of that which can be identified from this world—i.e. people, places or things. However, for most of photography's existence, there has been a parallel tradition of what is generally labeled "abstract photography," or photographs that purposefully stray from presenting things as immediately recognizable and veer towards the abstract.

In their extreme form, these types of images can be understood—to borrow a term from abstract painting—as "non-objective," or containing nothing that can be immediately recognized. (Such paintings have also been called "pictures of nothing." To be specific, the phrase was used by a critic to describe the works of J.M.W. Turner and also served to title a series of collected lectures on the subject of abstract art by Kirk Varnedoe, a former curator at The Museum of Modern Art, New York.)

In recent years, this tradition has seemed to attract exponentially more attention from artists. Maybe it is because we have too many (representative) images available to us online or it's a reaction to the huge popularity of large-scale, very realistic figurative work, or the influence of the abstract work of certain artists, like Thomas Ruff, on subsequent generations.

Arguably, some of the most interesting photographers working today create non-objective photographs or pictures of nothing. And it seems like there is a new way to explore/picture this subject/technique monthly. For what it's worth, a few of the tendencies could be understood as...

-An interest in light. For example, Alison Rossiter's imagery stems from her experiments with expired photographic papers and Barbara Kasten uses materials such as glass, mirrors, Plexiglas, and mesh, to make large-scale geometric sets, which play with shadow, light, and reflection.

-An interest in visualizations of math and science. For example, Thomas Ruff's cycles are inspired by 19th century science books and are based on visualizations of “cycloids,” mathematical curves that are the product of rolling one curve along a second, fixed curve.

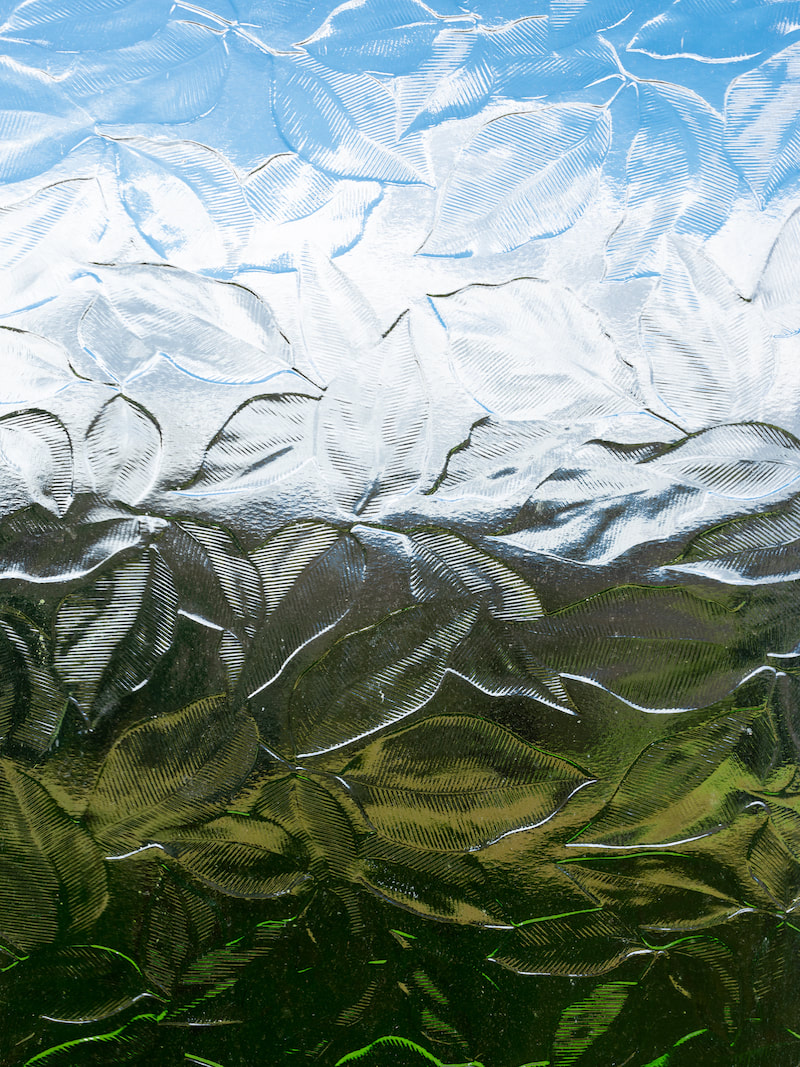

-An interest in focusing very closely on a typically-recognizable object to the point that it becomes abstracted. For example, Daido Moriyama's patterned monochromes are close-ups of legs sheathed in tights.

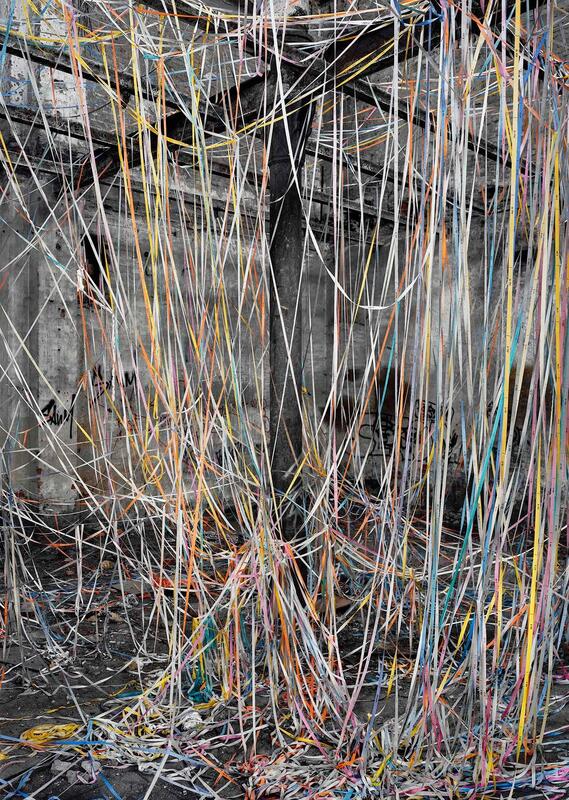

-An interest in decay and the photograph as a sculptural material as in Ryan Foerster's abstractions, portraits of friends he made that were destroyed (and inherently re-born) by the flooding and destruction of Hurricane Sandy.

-An interest in textures. See, for example, Frank Thiel's photographs of weathered buildings.

-An interested in abstracting history to encourage different perspectives. Farrah Karapetian's large-scale photograms focus on details of scenes and signs of protest.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

This second article has some additional information and resources.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed